Color Matching and Mixing explains Alfred Hickethier color theory and cube

Color can be subtle. It can be vibrant. It can be puzzling, maddening, and elusive. Color can be polarizing, leading us to proclaim our affection for or dislike of a given hue. But one thing we can all agree on is that color is difficult to talk about. Color resists our attempts to understand, explain, and describe it. In fact, for hundreds of years great thinkers have devised various methods and means of understanding color and the relationships between and among the various hues.

More...

We have a variety of color wheels, each with a subtle difference from all the rest, and we have both additive and subtractive models for obtaining a variety of different colors. The reason it’s so important to have a standard, reproducible means of both describing and creating color is that color can be subjective – or at least the way we interact with color can be. Your idea of a perfect spring green might look more like lime green to me. If we rely simply on words, we’re likely to end up going in circles.

Alfred Hickethier certainly had an interest in finding a precise way to describe and blend colors. He wanted to make lithography and printing in color more consistent, and he published his color cube – a three-dimensional model comprising 1000 individual colors – in 1952. Though there are more than 1000 possible colors, Hickethier believed that more than 1000 didn’t yield meaningful differences – that the human eye couldn’t really discern more colors than his cube contained.

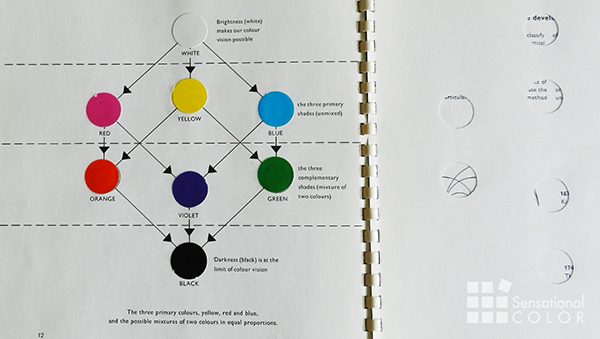

A page from the book Color Matching and Mixing shows the Hickethier color cube

Hickethier Color Cube

After Hickethier published the color cube, he published his color mixing system in 1963, and this system is a stunning translation of color – that slippery, vexing topic – into a crystal clear, remarkably simple numerical system. Here’s how Hickethier did it:

- There are three primary colors – Cyan, Magenta, and Yellow – along with white and black used to create every one of the 1000 colors on Hickethier’s cube.

- Hickethier’s system is subtractive, meaning that the addition of pigment absorbs and reduces some wavelengths of light.

- In the Hickethier Color Theory each color is assigned three-digit numerical values. The five basic color are White (000), Cyan (009), Magenta (090), Yellow (900), and Black (999). Every three-digit number indicates the proportion of Cyan, Magenta, and Yellow pigment used to obtain a given color. The first digit always refers to Yellow, the second digit to Magenta, and the third to Cyan.

- When you use pure pigment, delivered in measured drops, it’s easy to mix colors consistently. For example, Cyan uses 0 drops of Yellow, 0 drops of Magenta, and nine drops of Cyan. Orange (990) is 9 drops of Yellow, 9 drops of Magenta, and 0 drops of Cyan. Using the numerical formula – and adding black and white for darker and lighter color values – you can create Hickethier’s entire cube of 1000 colors – all with only five pigments.

How Hickethier Color Theory Is Different

So what differentiates the Hickethier color theory model from other competing or complementary models like Albert Munsell’s? Munsell’s model – both at first glance and on a deeper look – is far more complex in terms of its language. We have to understand the particular way in which Munsell used the primary aspects of color – hue, value, and chroma – in order to makes sense of Munsell’s color sphere. Hickethier reduced everything – all 1000 of his colors – to a mere three digits. He adopted a far less subjective language – numbers – to describe color.

By translating color into numbers, Hickethier achieved something perhaps no one else ever has – making color understandable in a completely objective (rather than subjective) way. When you think about the relationship among a set of greens, for example, understanding those relationships in terms of a different number of drops of Cyan and Yellow pigments greatly simplifies what differentiates one color from another by revealing the formula used to create each distinct color.

How Simple Is Hickethier’s Color Mixing System?

So simple a child can do it. It turns out that the most common pure use of Hickethier’s model is found in art classrooms. Using a curriculum developed by art teachers, Rock Paint Distributing, and Triarco Arts and Crafts, students learn to mix pigments, build color wheels, and discuss the subjective aspects of color, all using Hickethier.

While other color theories and systems – like Pantone – have gone beyond the work of Hickethier to regularize color across multiple applications and media – from textiles to computer screens – Hickethier remains relevant for the elegant simplicity of his important color cube and color mixing system.

So much of design involves developing a sensitivity to and a fluency with the language and relationships of color, and Hickethier provides a means of not just labeling color, but actually participating in the making of color. When you blend just the right shade of teal, you begin to hone your sensitivity to the subtleties of colors and their relationships in a way you can’t ever learn from a textbook. A deft touch with color demands a deep, nuanced understanding of how colors interact and play with one another. Blending five pigments to create a kaleidoscope of 1000 colors helps you consciously develop your color awareness and augments your color experience.

Have Fun With Hickethier Color Theory

Here is a fast, fun and easy way to put the Hickethier color theory into practice -- dyeing eggs with food coloring Using just three colors I'll show you how to make 18 different colors that you can arrange into your own egg color wheel.

Is there a fee for this class?